The beginning and history of the Extinct Birds Project

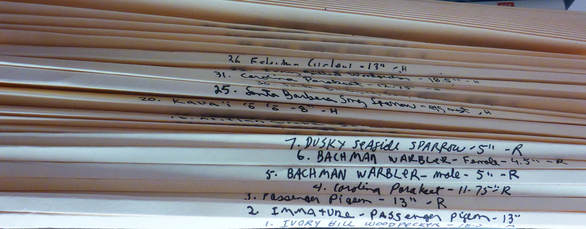

On the morning of June 30 in 2015, Jane Johnson, the Director of Exhibits & Special Collections at Roger Tory Peterson Institute in Jamestown, New York, began her tour of the museum’s archive. After walking into one of the several climate-controlled rooms in the museum, Jane started pulling out long deep shelves from the metal cabinet. I was unprepared for what I was about to experience. On the clean white paper that covers the drawer were the bodies of seven extinct birds and around a dozen other threatened species. I was transfixed by the skins. A tremendous veil of sadness laced every one of the specimens and countless questions immediately ran through my mind: How did these get here? How did they get the birds? I guess I’m glad they were collected, so I could experience this. Should they have been collected if they went extinct? Where were these birds collected? What was their lives like? Who collected them and how? What were the collectors thinking when they collected them? Have the bodies been gutted and filled with cotton? How do they do that? Why am I not as moved by the other birds in the other drawers?

The bound feet and cotton-stuffed eyes were particularly disturbing because it made it clear how each body had to be violated to prepare each skin. These skins seemed to be a perfect metaphor and reflection of the brutality that led to each species elimination. These birds, which had been killed, gutted, stuffed and laid out on a shelf, were a better reflection of their tragic story than those specimens that had been perched on a branch creating an aesthetic but artificial depiction alluding to them being alive.

On the morning of June 30 in 2015, Jane Johnson, the Director of Exhibits & Special Collections at Roger Tory Peterson Institute in Jamestown, New York, began her tour of the museum’s archive. After walking into one of the several climate-controlled rooms in the museum, Jane started pulling out long deep shelves from the metal cabinet. I was unprepared for what I was about to experience. On the clean white paper that covers the drawer were the bodies of seven extinct birds and around a dozen other threatened species. I was transfixed by the skins. A tremendous veil of sadness laced every one of the specimens and countless questions immediately ran through my mind: How did these get here? How did they get the birds? I guess I’m glad they were collected, so I could experience this. Should they have been collected if they went extinct? Where were these birds collected? What was their lives like? Who collected them and how? What were the collectors thinking when they collected them? Have the bodies been gutted and filled with cotton? How do they do that? Why am I not as moved by the other birds in the other drawers?

The bound feet and cotton-stuffed eyes were particularly disturbing because it made it clear how each body had to be violated to prepare each skin. These skins seemed to be a perfect metaphor and reflection of the brutality that led to each species elimination. These birds, which had been killed, gutted, stuffed and laid out on a shelf, were a better reflection of their tragic story than those specimens that had been perched on a branch creating an aesthetic but artificial depiction alluding to them being alive.

The Evolution of the Extinct Bird Series

I have tried to analyze why I was so moved and how I could create a body of work that would capture these emotions while trying to answer some of the questions that I had previously faced. It took me two years to start that series of paintings mostly due to another project I was working on in Nepal which helped shape how this website and project's publication would be researched, written, designed and published. This time also allowed me to carefully organize how the paintings would be exhibited, research how to construct each painting panel, and calculate the size and format for each painting. At first, the paintings were going to be presented in a vertical format and painted from an aerial view looking down at the skins. After realizing that in the larger paintings the head of each bird would be too far up and away from the viewer, I decided to change the format to a horizontal composition with a profile view of each bird. With this format change, the viewer could look into the eyes of the birds or, in this case, the cotton that had replaced the eyes. This change also meant that I would need to return to the RTPI and rephotograph the specimens. For scale, I wanted to include an object in the painting that could provide a consistent sense of size and scale across the series for the viewer. A burnt match was selected because of its commonality and possibility of acting as a metaphor for finality and expiration. The match, when given out at the exhibition, also served as an artifact for the audience to use when looking at the painting for scale and as a souvenir of their experience. To iconicize each bird and its importance, I multiplied the size of each specimen and the match by 2.61 times.

I have tried to analyze why I was so moved and how I could create a body of work that would capture these emotions while trying to answer some of the questions that I had previously faced. It took me two years to start that series of paintings mostly due to another project I was working on in Nepal which helped shape how this website and project's publication would be researched, written, designed and published. This time also allowed me to carefully organize how the paintings would be exhibited, research how to construct each painting panel, and calculate the size and format for each painting. At first, the paintings were going to be presented in a vertical format and painted from an aerial view looking down at the skins. After realizing that in the larger paintings the head of each bird would be too far up and away from the viewer, I decided to change the format to a horizontal composition with a profile view of each bird. With this format change, the viewer could look into the eyes of the birds or, in this case, the cotton that had replaced the eyes. This change also meant that I would need to return to the RTPI and rephotograph the specimens. For scale, I wanted to include an object in the painting that could provide a consistent sense of size and scale across the series for the viewer. A burnt match was selected because of its commonality and possibility of acting as a metaphor for finality and expiration. The match, when given out at the exhibition, also served as an artifact for the audience to use when looking at the painting for scale and as a souvenir of their experience. To iconicize each bird and its importance, I multiplied the size of each specimen and the match by 2.61 times.

These two years also allowed me the opportunity to increase the breadth of the species investigated for inclusion into the painting series and the book. With the assistance of Dr. Twan Leenders, the president and executive director of the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History, I was able to contact Dr. Jeremiah Trimble, the curatorial associate and collection manager in the Ornithology Department at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. Through efforts of Dr. Trimble and curatorial assistant, Dr. Kate Keldridge, over two dozen extinct bird skins, eggs and nests were made available to be photographed by me and my son, Diego. Other museum collections were investigated and it seemed, strangely enough, there were no shortage of extinct birds collections available around the country and internationally but time and scheduling made it difficult to investigate other institutions.. Eighteen birds skins were selected for inclusion into the initial painting series and book. These species were curated by variety in size, global reach, popularity and reasons for extinction.

A l b e r t o R e y w w w . a l b e r t o r e y . c o m a l b e r t o @ a l b e r t o r e y . c o m